LeadDev London 2023

It was my first time at LeadDev, and I had a great time! I was very thankful to the organisers for gifting me a ticket and making it possible for me to go!

My partner Anna had already had a ticket, after wanting to go for a couple of years now, so I was fortunate to be able to tag along, and it meant that at least I'd know one person there, although we did end up bumping into a couple of folks we knew.

There's a great highlights video for a sneak peek into the conference, before you start digging into some of the talks I've written up below.

I really enjoyed the mix of Meri Williams as the official MC introducing speakers, and Amber and Jessie of Glowing in Tech being the experience hosts, keeping us updated on the event's schedule, talking about the socials, various excellent food breaks, and sharing information about sponsors.

I also liked the fact that there was a good set of stickers for pronouns, and also as to whether you were comfortable with physical touch (i.e. handshakes) and that there was still a good amount of COVID precautions in place.

I had a lot of time speaking to the sponsors on their stands, including some folks who were incredibly persistent at trying to get Deliveroo to trial their software 😅 One of the prize draws required speaking to sponsors to get a letter that would combine to spell a phrase, of which we managed to get enough letters to then guess the full sentence, Wordle-style.

The conference was packed with talks and had some really incredible speakers, topics and thoughts. I really enjoyed the mix of talk lengths, allowing a sprinkling of shorter talks, alongside longer talks, and all of the talks were really polished 🙌

I was also a huge fan of "speaker office hours" which was an alternative to Q&A at the end of the talks, where it allowed asking questions directly to the speakers, with less of an audience (avoiding the "this isn't a question, but") and gave more of an opportunity to deep dive into conversations that wouldn't be possible in a regular Q&A.

The below talk write-ups are largely notes I've taken from the speakers, interspersed with comments of my own, and I'd be happy to hear if I've misinterpreted or misrepresented anything.

Managing at the Threshold: Examining our Principles in a Moment of Change

David Yee kicked off the day by discussing how we're in a liminial space, poised to be going into a moment of change, and that no one can tell you what to do because no one knows what's coming next.

David noted that liminal spaces can be thought of in terms of how you often remember "the event" (no, not the That Mitchell and Webb Look sketch) like a significant birthday or graduation, but not the time leading up to it.

David spoke about how a similar time could be seen around 2009, when we had a chance in engineering leadership in the industry, in a period of change around the economy, company operating models, and products available.

(image courtesy of Cat Hicks on Mastodon, as the angle my photo at wasn't very good!)

David shared that we should take on board four skills, which give us the ability to care about something, and bring something new into the world:

- notice

- think

- persuade

- proceed

David's slides and storytelling was excellent, and a great start to the conference, and I especially loved that we mostly ended on the thought:

do the right thing

Compassionate on-call

Lisa Karlin Curtis spoke about how being on-call can be stressful, but that it doesn't have to be.

Lisa told a story about being on-call while at a wedding, receiving a callout and while dealing with it, missed the best man's speech and her ice cream had melted. Lisa noted that life shouldn't have to stop while you're on-call, and if you were to have a "culture of overrides", getting short-term cover should be able to make things easier. But she did note that you should be cautious to putting a lot of focus on folks covering shifts as we want to avoid fostering a culture of hero worship or to make people make it seem like they're being a martyr, when really it's just about helping out other people.

Lisa noted that rotas should be sufficiently large, and that generally you should be compensated for time on-call, rather than having it just part of your salary.

Lisa shared a story about a time where she was on call for two incidents, and had the realisation that "that happened on the first day of last month too", exasperated that the issue had not been fixed in that time. As many folks probably empathise with, Lisa was told that "another team owns that, we can't do anything other than tell them it's an issue, again", much to her dismay. She shared that teams need levers they can pull to make changes, and that without the ability for teams to be empowered to fix things, even things that they don't directly own, being on-call will be getting more and more frustrating.

Lisa also shared a story of a time where she was involved in an incident relating to a potential data breach, and that neither her nor her manager had any idea what to do to handle the situation. As they were out of depth, they ended up calling in the CEO who was then aware of what process and communications are necessary, allowing the engineers to do the engineering work, instead of dealing with communications. Lisa shared that engineers need the support to deal with incidents, and to be empowered to use the ability to escalate - it can be a big thing to page a senior executive in the middle of the night, but it's a trade-off - it's better to be unnecessarily paging (within reason) compared to escalating too late.

Lisa discussed the alert fatigue and pager load that can be seen by folks, and that if your team is finding that they're being paged quite a lot, you should be looking at whether you can review recent alerts, working out which issues can be fixed, which alerts are actually false alarms and erode trust, and make steps to improve the experience for everyone. Sleep is very important, and can leave folks feeling groggy at a minimum, but resentful over time. Following on from an earlier point, Lisa noted that we should look to encourage someone else to take the pager to prevent someone who's been up all night have the risk of another page, or look at different options like "follow the sun".

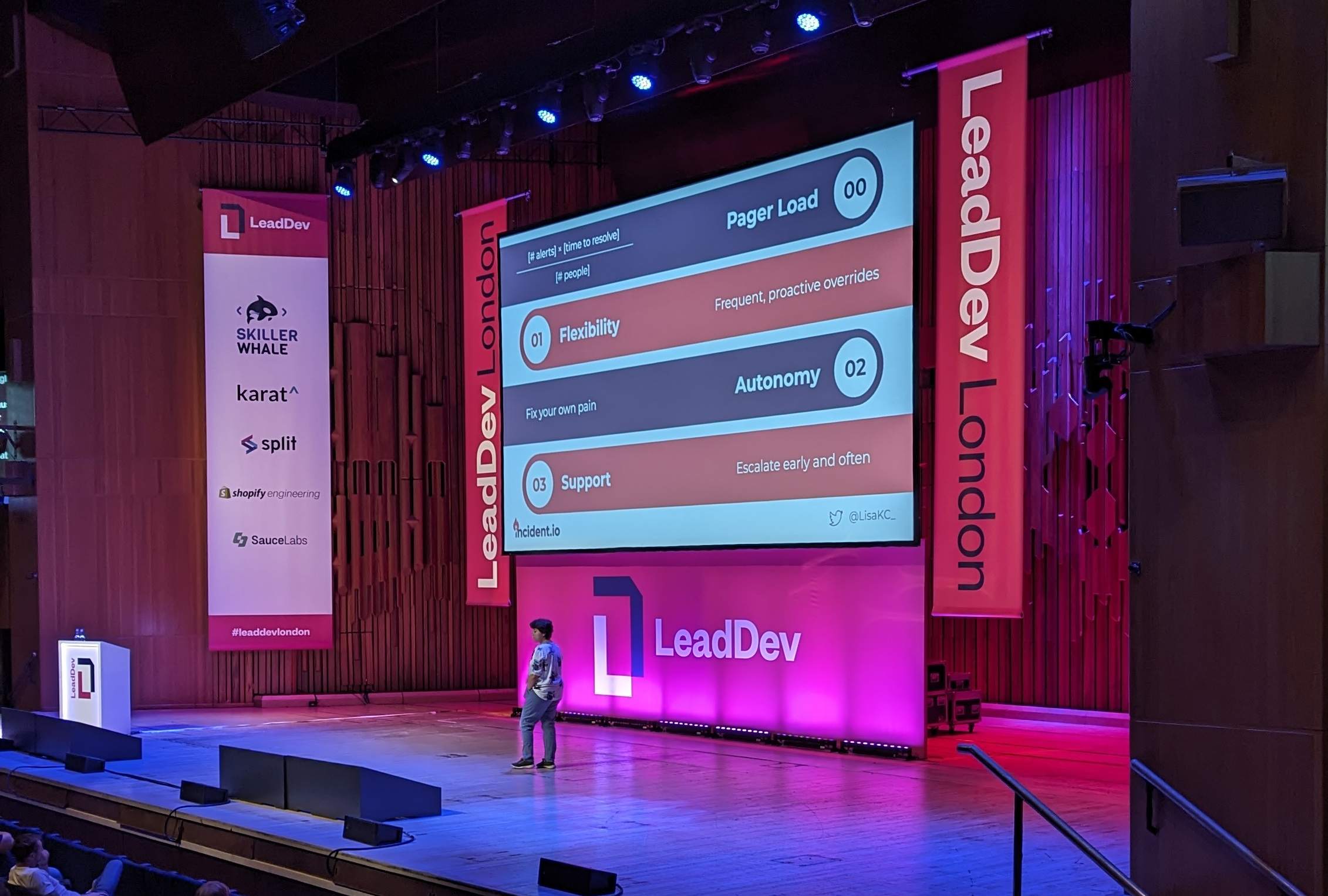

Lisa summarised her talk with the following slide:

Something I really liked about the talk was that I was nodding along with all of the points, both because I believe them, and because my team at Deliveroo is already doing a lot of them. I'm hoping to get a blog post out (on the Deliveroo engineering blog) to describe what it's like to be on-call at Deliveroo, as I feel it'll be helpful, and it's been on my TODO list for some time 😅

Red 2.0: Transforming a Game Company

Colin Walder shared the experience over the last couple of years to transform the way that CD Projekt Red build games.

It was an interesting story around the way that the organisation restructured off the back of the release of Cyberpunk 2077, which received very poor reception.

Colin discussed how, off the back of this, the teams both naturally and purposefully changed, and that the disappointing release of Cyberpunk 2077 was a great motivation for change across the company as a whole. He discussed how the organisation made their values explicit, not implicit, working hard to make sure that the team aligned to the values, or if not, would be asked to leave the company.

Although there's still a few months to go until Cyberpunk 2077 Phantom Liberty is released, things seem to be going positively, and Colin notes that if it's released on time, with the quality that the team and players want, without resorting to any crunch, then it'd be a great place to say that the transformation is going well.

What do you mean there's no onboarding plan for engineering managers?

Daniel Korn shared how often companies have a pretty well-refined onboarding processes for engineers, but forget about engineering managers, and shared work he's done to produce a four-week onboarding process that targets engineering leaders.

Daniel talked about how it can be hard starting as a new engineering leader, sometimes moreso if you've been part of the organisation before but are new to management, as well as external hires finding their place in the organisation, and that poorly onboarding new hires - in any job family - can lead to setting up folks for failure, instead of making it a place they can achieve and feel belonging to.

This culminated in a four-week plan, which has iteratively improved over 3 cohorts of new starters, which aims to provide a more reasonable onboarding, with a short timeline and achievable results out of it to set folks up for success. Daniel shared that he's found that making the plan super adaptable is important, where the learning path is shaped to each manager, allowing folks who are newer to line management to get more experience in what they'll be needing to do or allowing folks who've managed for 10+ years to skip the "new to management" track and focus on how they can embed their skills best with the organisation. Managers have a buddy and join in a cohort, so have a lot of support to help make it best, as well as their own direct line manager.

I really enjoyed the way that Daniel shared that the onboarding plan was split between "sessions" and "experiences", allowing the former to be a chance to absorb some knowledge, and the latter being an opportunity to practice what you've learned. These were described as a way to reduce the "firsts" that people experience, allowing a manager to practice reviewing i.e. setting goals off the back of a year-end review, but instead of waiting until the next time that happens, doing it off the back of the most recent case.

Code is Poetry

Niranjan Uma Shankar spoke about the importance of writing readable code, and its ability to make it easier to maintain your software by building a culture of writing clean code.

Niranjan explained that although it'll slow delivery at the beginning, making the mindset shift from "it works" to "it works and is maintainable" is really key long term, and allows you to focus on strategic programming rather than tactical programming. By investing a small amount of time on a regular basis, such as increasing your project estimates by 10-20% to allow for time to focus on these improvements, be it on the code we're building now, or for opportunities in existing code. Something I've found that's super useful is the concept of Prefactoring: Preparatory Refactoring to make it more intentional a process, and working in a team where this is not only possible but advised is a real superpower.

Niranjan mentioned that we should normalise nitpicking, in a nice way, to improve the maintainability of the code. One thing I will always do is codify the nitpicks, whether that is adding a new rule to our code style or enforcing larger architecture decisions. I find it's good to have these discussions, but generally only once, and then we can make sure that they're automated next time, as it's a waste of human reviewing time to nitpick syntax instead of thinking about the real functionality of the code.

I liked that Niranjan mentioned that we should be rewarding and recognising the work of folks in writing the more maintainable code, rather than just getting it out on time, making sure people have time and appreciation for doing strategic work. Not only does it incentivise it, but it normalises and makes sure that this is the sort of thing that can be seen as something positive for performance reviews.

Why Onboarding to a Company's Legacy Codebase Sucks, and How to Make it Work for Your Team

Shanea Leven of CodeSee spoke about how onboarding to (legacy) codebases can be hard, but that there are better ways to do so.

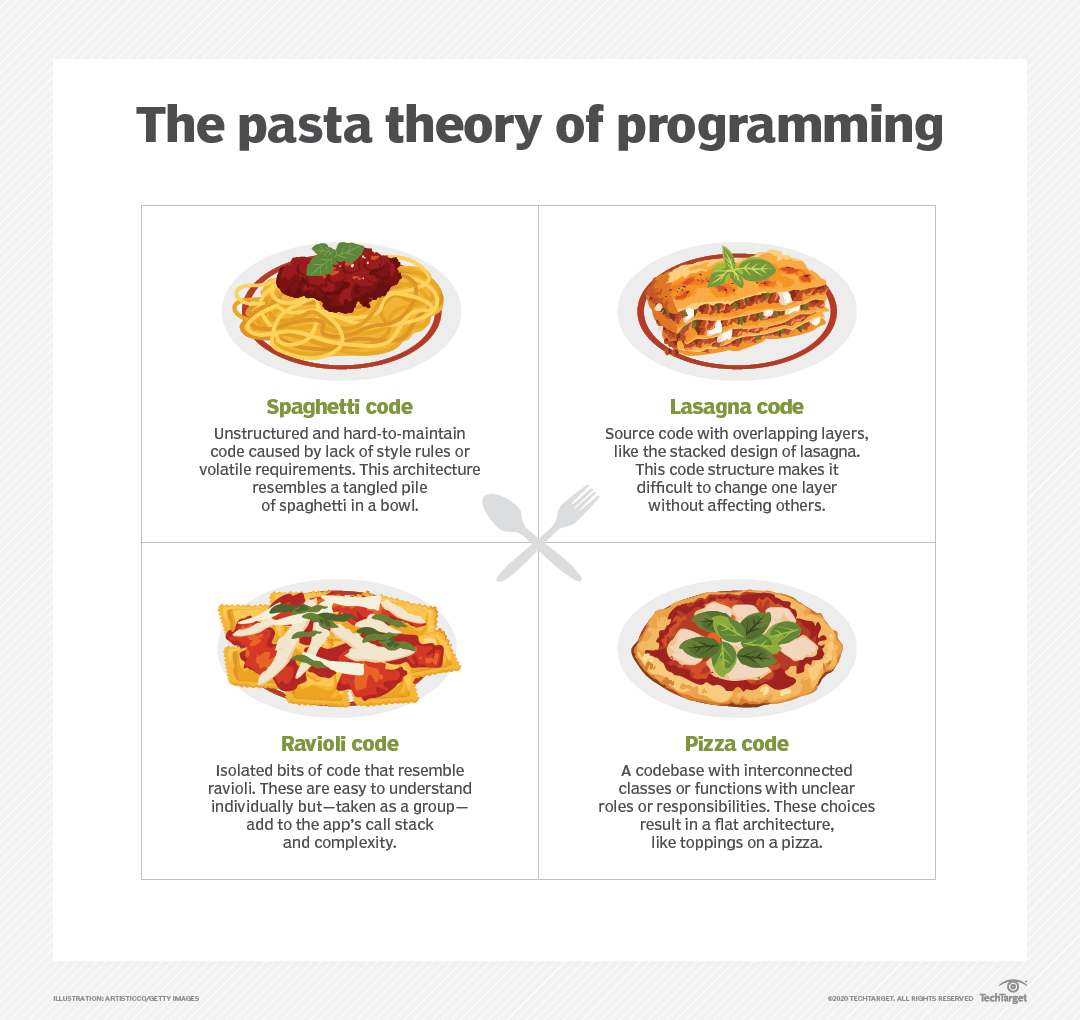

Shanea shared this image of "The pasta theory of programming", joking that every team has their own plate of spaghetti code:

A lot of folks learn by doing when onboarding to a new codebase, so can start by working on smaller tickets, and then as their experience grows, can pick up more significant features. Working on delivery with the team is a great way to learn conventions around the code itself, but also how the team does code review, design, testing, deployments and releases, as well as any known gotchas in the codebase. And although one option was that you could constantly be pairing with a more experienced member of the codebase, it's not very effective, and will reduce the velocity of your team, as well as being incredibly exhausting!

Shanea mentioned that in the last 50 years we've not really improved the way that we learn about cod - we're still doing the incredibly inefficient process of reading through the code line-by-line.

And although we may think that onboarding is a one-time thing, it can't possibly be, because our codebases are constantly changing with new features, incidents, refactoring, as well as the impact of our team restructures and folks joining/leaving the business. It's incredibly unlikely you have enough time in the day to look at every change going into them, so we are going to be continuously onboarding.

Shanea had three types of advice, pitched at the team, onboardee, and for continuous onboarding. The key takeaway was to start small, with tasks the team know well and can support on, pick up isolated features or tech debt and small improvements, learning how the domain objects interact, how the system is architected, and make sure you're continually refining the process because you will be consistently re-onboarding! Shanea shared that it's a good idea to read, but not trust, documentation as it can be out-of-date, but to continually keep that documentation up-to-date where possible.

However, even with all of this, we're still being fairly inefficient, so we need better tools that work for us, allowing us to understand our codebases faster than we can do so with just humans in the loop, whose knowledge may be soon out-of-date anyway. Shanea shared CodeSee's insights into different types of applications, understanding the use of database queries, infrastructure and vendors, as well as getting visibility across different source repositories.

Making the Move to Manager: Common Pitfalls for New Engineering Leaders

Jacqueline Pan and Marlena Lui shared what they've learned since recently moving into management, with a slightly different path to getting there.

Jacqueline explained that she has been navigating how to redefine relationships from being one of the engineers in the team to now being the engineering manager, both in terms of the change in relationship with colleagues and the way that she now has to take a step away from the code and nitty gritty details she knows so well.

Marlena explained how she'd moved into management through a team change, leading to her having to upskill in a new tech stack, domain, and get to know the team.

I really liked the way that the slides were presented, matching Jacqueline and Marlena's positions on stage, and providing both sides of the topic at hand.

Firstly, we heard about relationship building.

Jacqueline mentioned that she had to deal with the change in relationship with the team, needing to push the team away (nicely!) to create boundaries, such as no longer eating lunch with them. Jacqueline mentioned how trust is the definition of these relationships, and she wanted to build that strong foundation up to make sure the team were aware of what her intentions would be if there were hard decisions to make. She mentioned that it's OK to be yourself, just remember the new power dynamic.

Marlena mentioned that coming straight into a team fresh, she didn't have much time to slowly build up the relationships, and instead had to jump straight in. Marlena wanted to come in and know everything to be able to lead the team, but through that has learned that it's important to show the team that you're able to say "I don't know", as a way to build trust, and because it's hard to be able to know everything even when you've been in the team years!

Next, we heard about delegation.

Jacqueline mentioned that delegation is a skill, but a crucial one to learn, especially as a manager. She'd continued doing what she was doing as an individual contributor (IC) for a bit, robbing the other ICs in the team of opportunities to learn and grow. Jacqueline mentioned that it's important to know where your time is best spent, to do things that others can't, and suggested dividing up your work into what can/cannot be delegated, and go from there.

Marlena continued her mention about wanting to know how to do everything, and that she didn't feel it was "fair" to delegate if she didn't know how much work was required to do the task. Marlena's learned that it's important to know what level you're expected to know things, and at what point it's not necessary.

Next, we heard about "managing up".

Jacqueline went into the role thinking that managing up as a manager would be the same as an IC, but realised that she needed to start managing the vision for the team, rather than a personal side of things, as well as a healthy amount of own focus on your own career, which requires trust and overcommunication with your manager.

Marlena mentioned that at the time she was promoted, so was her manager, so she couldn't lean on her manager for as much support as they were also dealing with a new role. She mentioned that there was a bit of a negotiation dance, working out when to lead/follow and collaboratively make decisions.

I thought this was a great talk and super recommended for anyone about to start managing or as a new-ish manager.

"I'm happy where I am" - Supporting team members that aren't seeking progression

Ryan MacGillivray spoke about how not everyone wants to chase the next promotion, and sometimes want to stay where they are.

Ryan shared this quote by Kurt Vonnegut:

The practice of art isn't to make a living. It's to make your soul grow.

With this, Ryan discussed the myth of constant promotion and feeling like you're always needing to go for what's next. Not only is it unfair to constantly be expecting folks to be looking at the next step, but it may also not be possible - there may not be a next role, or there may not be a space that you can fit into, or get the opportunities you need to be able to show you can take the next step.

It's also fairly unsustainable to always be pushing yourself, which I agree with as someone with ADHD whose free time is mostly filled with side projects that are mostly the same as my day job 😅

As someone who's recently decided that their next promotion in their team isn't quite where they want to be going (yet), I empathised a lot with this talk, as well as having fairly regular discussions with other folks at different levels who are happy where they are.

Ryan shared this quote from Radical Candor:

Make sure that you are seeing each person on your team with fresh eyes every day

Ryan shared that it's important to make sure that every member of the team is valued, and that we need to show them that there's space for them in the team without pushing them up, or out. Ryan went on to mention how a member of the team can be continuing to mentor or coach, will likely have a lot of learning to do in some areas of the team, and could take the time to become a domain expert. He warned us not to deprioritise folks who decide this, as some managers may do, instead focussing on those who are looking for growth.

I also loved that he recommended we celebrate things other than promotions, suggesting that leading big projects, coaching others, or delivering the fix for a gnarly bug fix is important.

Ryan mentioned that for folks who aren't looking to move, it may be one of two things - could they not want to get that next promotion, or do they feel they'd not be good at it? He mentioned that it's possible to give them the experiences that can then help them understand if they do want that role, moving from a feature lead to a Tech Lead. It's possible that someone may not want to stay as a Junior/Mid-level engineer forever, but there will absolutely be reasons, so it's worth having open and honest discussions about it.

We can encourage them to seek progression, but make sure that it doesn't make them feel like there's no space for them, or that we're pushing them out. And most of all, we only want to encourage them to seek the promotion if we think that not doing so would be acting against themselves - if we can see they may not be ready for it, or it may not be the best fit right now, don't do it.

How to drive pace in your team 🏃🏽♀️

Alicia Collymore shared how to work on driving pace in your team in a sustainable way.

Alicia started off by explaining that "pace is value delivered at speed", with focus on the "value".

She noted that she could not use common measurements about using productivity metrics due to the way they can be gamed, as well as the fact that working in a small startup it's much harder to have consistent data.

Instead, Alicia found that setting the team defaults and trying to keep motivation high were a good starting point. By putting pace at the heart of the team, and creating hype to make the team excited by the impact and value of the work they're doing, that can help keep things going. Additionally, give the team lots of room for autonomy, allowing the team to run the projects and make hard technical or product decisions, being there to challenge and ensure the right thinking is in place, but allowing them to move quickly without waiting for lots of approvals. Finally, Alicia mentioned that transparency by default is important, making sure that discussions are open and visible i.e. in Slack channels, where there are regular project updates and Engineering Managers can jump in if things need a bit of support.

Alicia also mentioned that it's a good idea to optimise your projects, suggesting you focus on keep them at a very short lifetime, such as a matter of weeks, so value can be released to customers as soon as possible. Incident.io are generally a fan of keeping things simple, which means that it's easier to find resources and knowledge from others, and if things go wrong it can be easier to recover if you're not doing anything too clever or complex. She suggested to try and do the hard bits first, making sure that unknowns are tackled ASAP to give you a chance to regroup if anything needs to be changed. Alicia shared that "work done is better than work started", and that we should strive to finish what's in flight instead of starting a new thing, which is always a good thing to strive for. Finally, Alicia mentioned that regrouping when things change, such as someone's off sick or there's a complex roadbump, which allows for an early opportunity to decide the plan and scope, working to reset expectations, the associated deadlines and determine if any scope needs changing.

Alicia also suggested you should encourage individual pace, working to find the superpowers in the team and collectively take advantage of them. An interesting suggestion from Alicia was to focus on beating your deadlines, for instance try and beat the estimate on the ticket, and then ask the team if they think it's worth you leaving the ticket there and helping someone else get their work done, or if you have time to improve/refactor the work you've done. In a similar vein, Alicia noted that engineers like to dig and dig to try and solve a problem if they're stuck, and aren't necessarily the best at asking for help. Instead of letting this happen, potentially with someone getting a bit demotivated and frustrated trying to solve a problem, that we should make the environment one where they can ask for help earlier, and collaborate on solving the problem rather than trying to best it themselves. And finally, it's expected for things to go wrong and be painful - make sure everyone's talking about things and seeing what you can learn.

Speaking of what can go wrong, Alicia talked about the different ways focussing on pace can be a detriment to the team. Too much pressure can be put on the team, so it's up to managers to make sure that we see if we can relieve pressure, such as resetting external expectations for work if things are running late, and communicating that the deadlines are (generally) fine to shift! A common victim of the focus on pace is poor code quality, to which she mentioned to try and avoid the compromise, and still focus on performant and resilient code, which tackle the main use cases for your problems. In the case that you do need to compromise, make sure it's an active trade-off you're making and agreeing with, instead of it just happening silently or implicitly. Alicia noted that we don't want to breed an unhealthy competitiveness across the team, where some folks may think they're better because they're delivering more tickets. Another problem is that instead of focussing on value, you just focus on speed, which means you're possibly shipping the wrong things to customers. Similarly, just because you're delivering at pace doesn't mean you're doing it sustainably, and you may instead have a false sense of speed because you're over-optimised the work, or you've got engineers burned out and/or doing a lot of overtime.

Finally, Alicia talked about how important it is to understand your limits and know your boundaries. It's important to know the limits to your flexibility, such as wanting to have good user experience, but not worrying if you don't have pixel perfection, and what you're willing to compromise on. It's also important to be explicit with your team on what you want from them i.e. "do whatever it takes to get it over the line, including unlimited overtime". And finally, make sure that this is all written down and discussed often, embedding these decisions and culture into the team.

Alicia recapped with the following key takeaways:

- get the team on board and make sure you set expectations

- optimise your projects, keeping them short

- encourage individual pace inside the team and find and utilise superpowers each team member has

- understand the limits in the process, and what you can and can't compromise on

How we support making architectural decisions

Olena Sovyn shared how Webflow approaches technical design with the Technical Design and Architecture Advisors (TDAA).

This was another talk that resonated with me, and was nice to see how similar it is to Deliveroo's Engineering Design Peers, and I especially agree with the fact that you want peers and practitioners who are reviewing your designs and architecture.

Where we're going wrong with developer productivity

Cat Hicks shared a really great talk about how a lot of the measurements commonly used to measure productivity are flawed, in a talk filled to the brim with graphs, stats and interesting observations.

Cat started off by asking the audience to raise their hand if "they are productive", at which a good chunk of the audience raised their hands. Next, she asked folks to raise their hands if they felt they were "more productive than the person next to them". Finally, we were asked to raise our hands if we'd helped someone recently. Cat used this as a point to note that we don't know how to measure productivity, and when we're using questions somewhat like this, we're not measuring what we think we are.

Cat noted that in a survey of engineering leaders, 88% believed that they're making their team's work visible, which is at a stark contrast of the engineers being asked the same thing, where only 24% believed the same! Cat joked about, being a social scientist, she gets very excited by misalignment in data, and found this interesting to dig into.

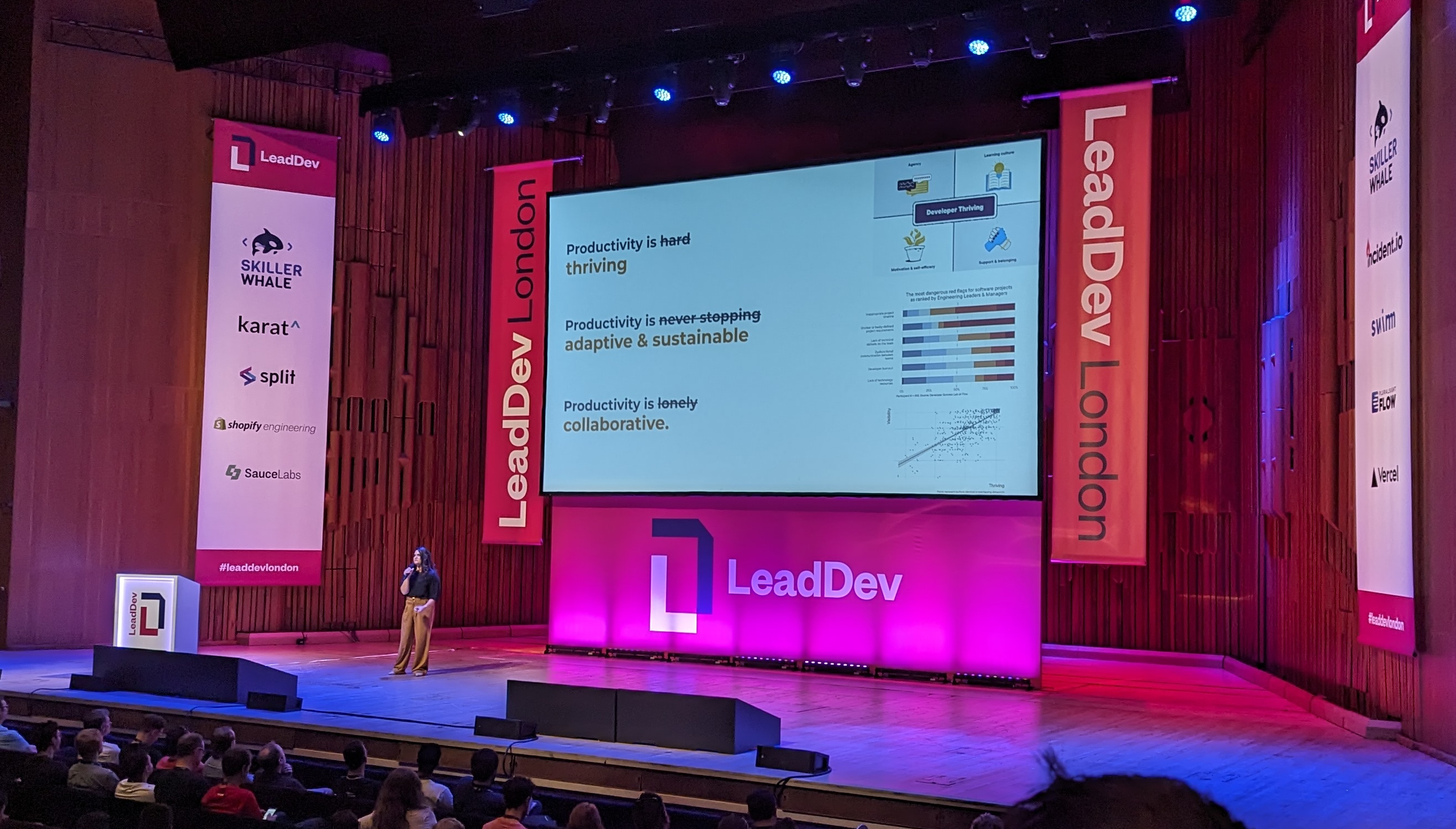

Cat discussed how:

- productivity is hard - people are constantly learning that working faster is better than working better

- productivity is never stopping

- productivity is lonely - a lot of discussion is around how we should "leave engineers alone to code" and cancel meetings and allow them to focus, but we're also not giving them time to experiment and collaborate

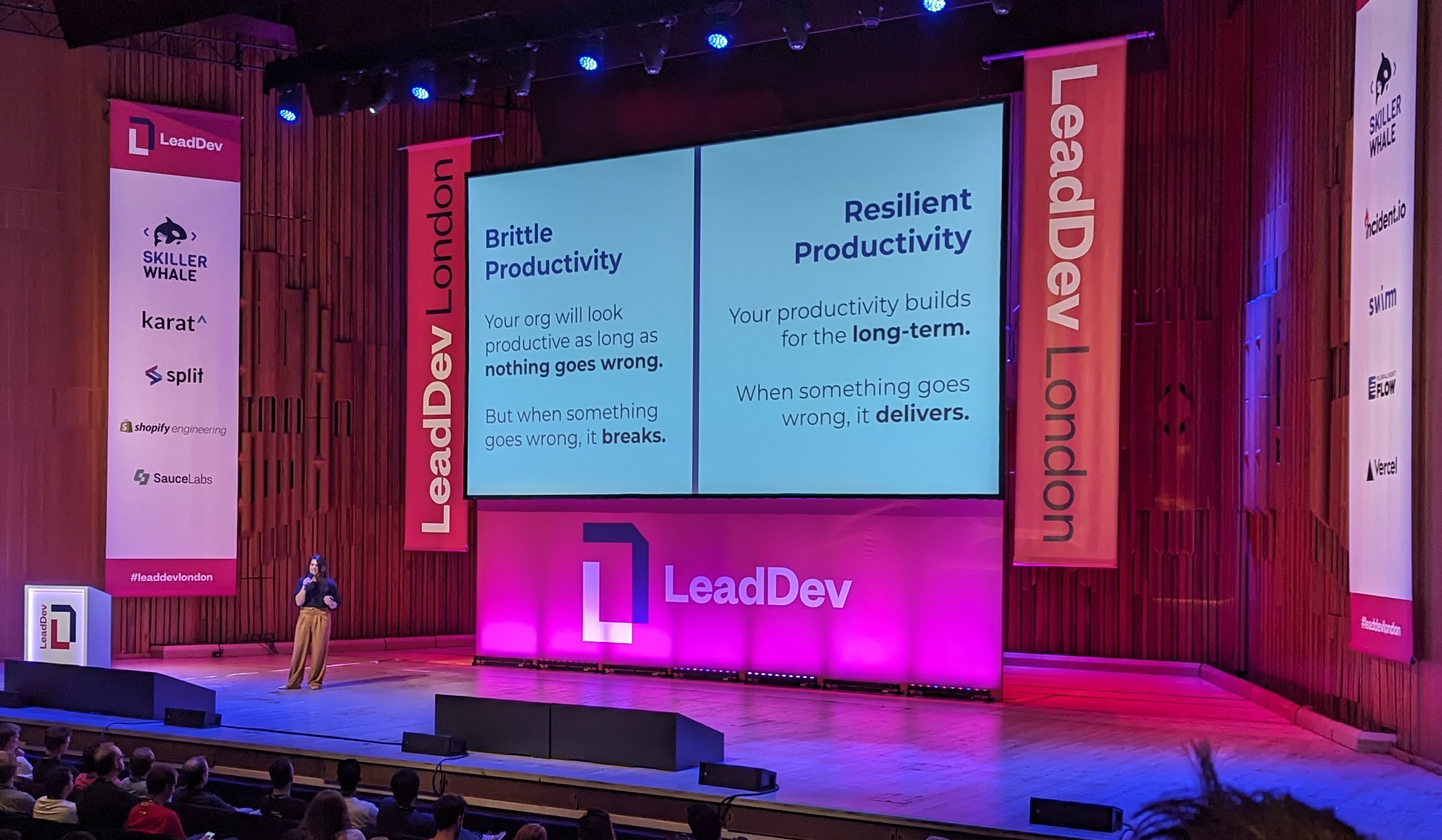

Cat went on to do discuss brittle productivity vs resilient productivity:

Cat noted that brittle productivity is worse than folks just being disengaged, because it looks like you're being productive - until you realise you're not - and can be hard to spot.

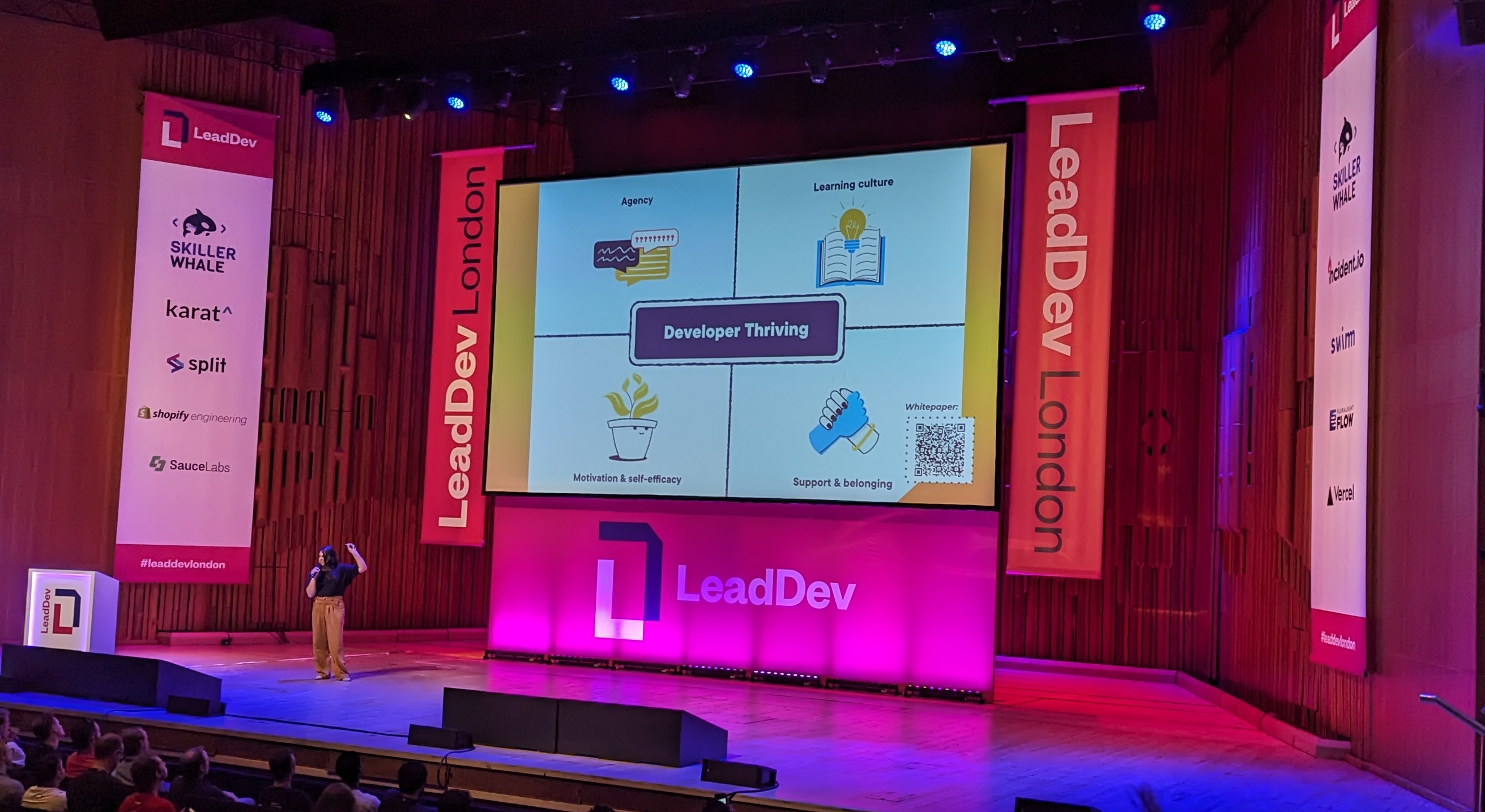

Instead of measuring productivity, Cat suggested that we instead focus on Developer Thriving:

Cat noted that thriving is significantly better at predicting productivity at scale, and also focusses on things that are generally better for engineers anyway.

Cat reviewed the above statements about productivity with the following slide:

She noted that productivity comes from thriving, and can be unlocked by doing work that feels good, and fits within the four factors of developer thriving - Agency, Learning culture, Motivation & self-efficacy and Support & belonging.

Cat discussed that we should be using things like retrospectives and 1-1s with our managers to surface issues. Cat noted that when teams fail to deliver, experienced engineering managers will hit the pause button and investigate what processes in use aren't working, and use the changes in process to improve developer thriving.

Finally, Cat noted that productivity is collaborative, and we should be working to make sure folks don't feel like "all" we want from them is churning out code in isolation, we should be building a relationship between teams and their organisation and helping them understand why.

Cat's talk was excellent, and for very good reasons she's snagged quite a lot of requests to speak at other events!

This talk was especially interesting as Deliveroo have just adopted looking at Developer Productivity metrics, and there seemed to have been a lot of cases Cat's talk mentioned "don't do this" that we've looked at doing 😅

Cat shared the following resources to dig into the work she and the team have been doing:

- Developer Thriving White Paper Series

- 4 Tips Developers Can Use In Their Next Job Hunt + Example Interview Questions

- Developer Success Lab

Cat noted that at the moment, a lot of teams are being asked to "do more with less", to which Cat reminds folks that the laws of physics still apply. If we're not giving teams more budget, support, additional people, or improving the human experience at work, it's not going to work out.

Cat left us on the note that the most dangerous choice right now is whether we're building our organisations on top of brittle or resilient productivity.

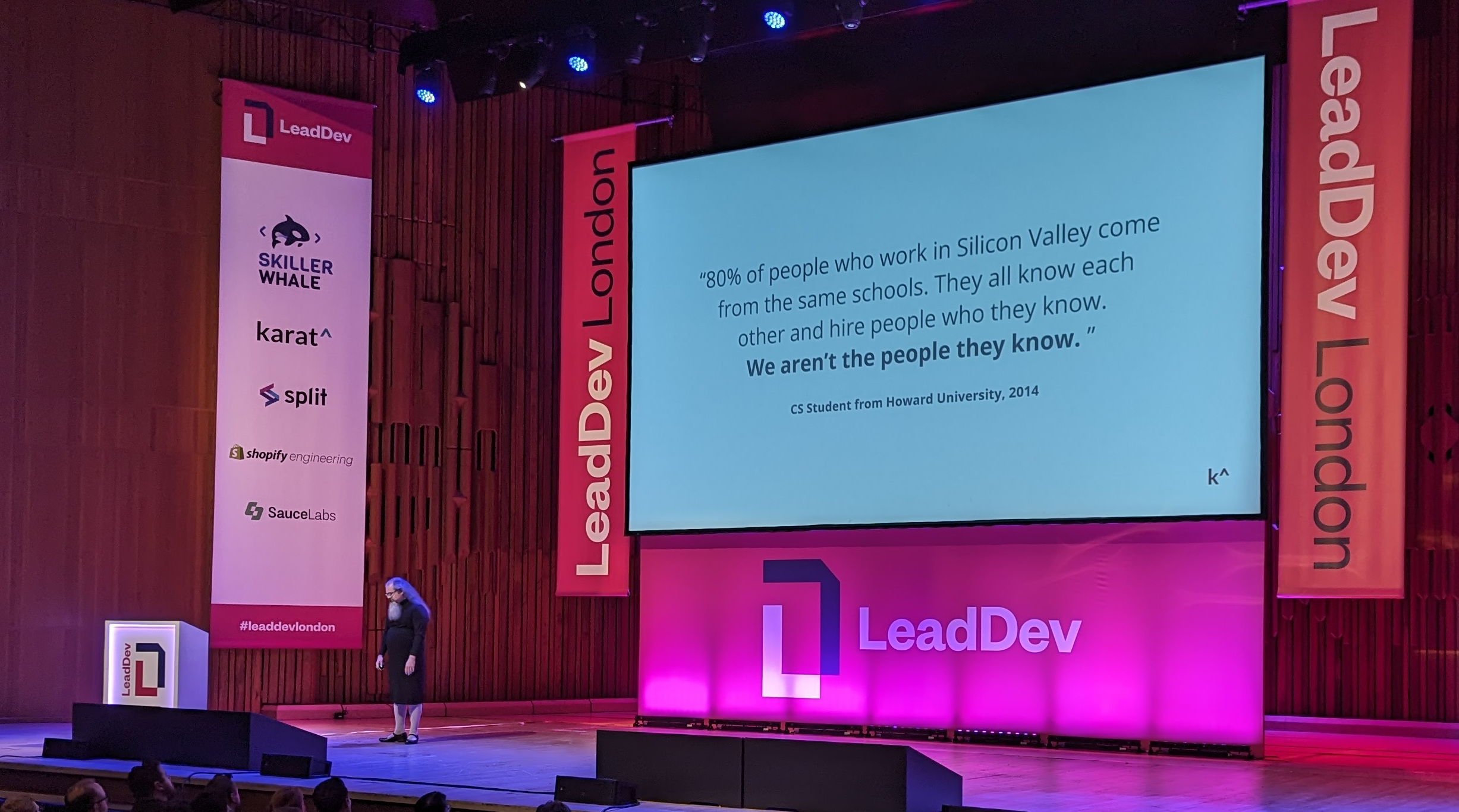

Engineering a more equitable hiring process

Jason Wodicka shared a really interesting talk about making the hiring process more equitable, and noted that an alternative name for this talk could have been "finding the right candidates efficiently".

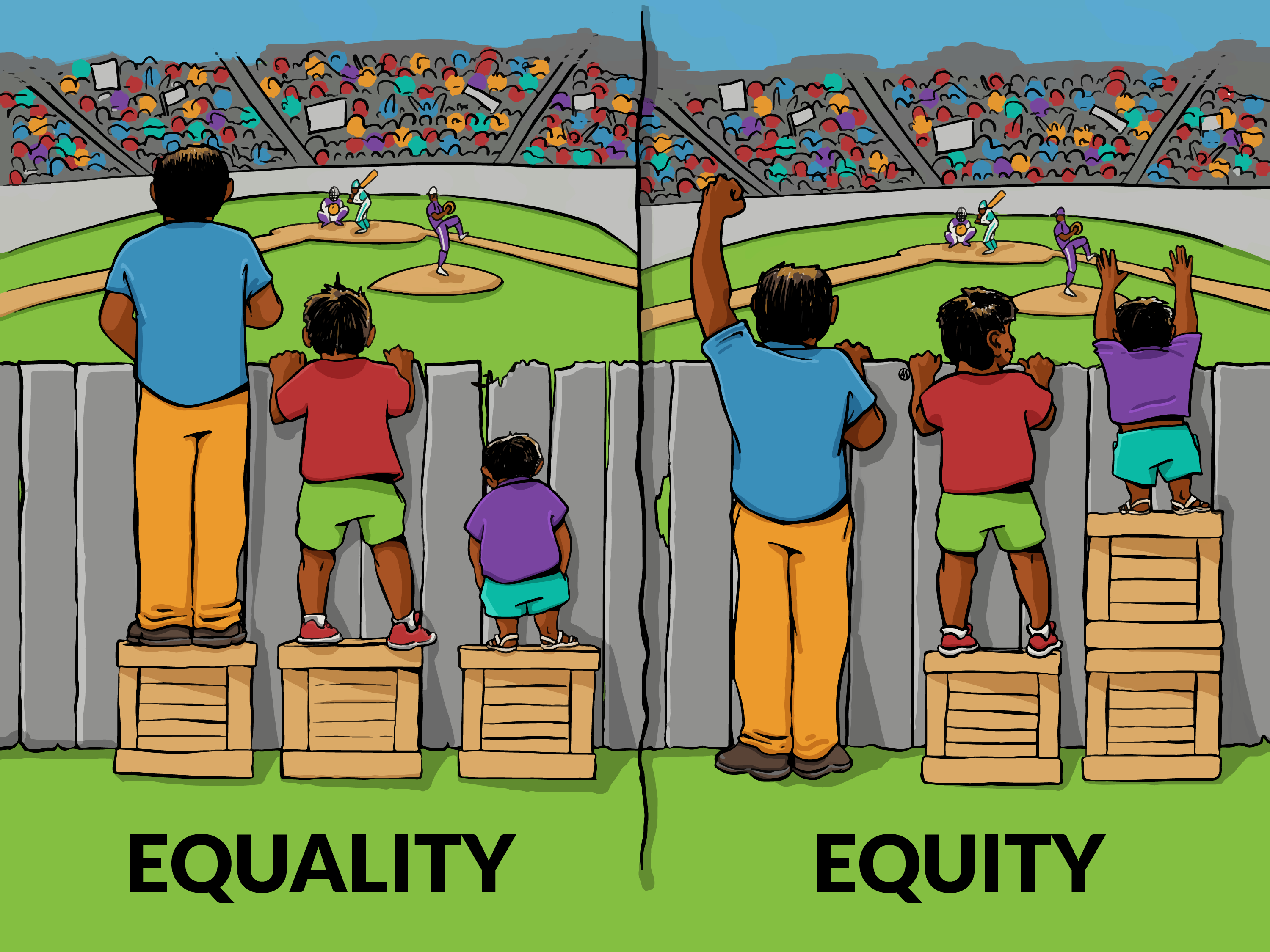

They started with a visual explained about the differences between equality and equity:

Jason mentioned that in this case the boxes are still just a workaround for the fence, when really we'd want to break down the fence, which in this analogy would be the history of bias.

Jason recollected a time where they were asked whether they could comment on "is this candidate diverse", to which they made clear to the audience that there's no such thing as a "diverse hire", and that if you're looking at it from that angle, you're more likely to be seeing diversity as a finish line, rather than something that we continually do for the betterment of everyone.

Jason commented that a common problem is the streetlight effect:

A policeman sees a drunk man searching for something under a streetlight and asks what the drunk has lost. He says he lost his keys and they both look under the streetlight together. After a few minutes the policeman asks if he is sure he lost them here, and the drunk replies, no, and that he lost them in the park. The policeman asks why he is searching here, and the drunk replies, "this is where the light is".

With this, they elaborated that organisations may continue going to their usual sources of candidates such as Ivy League colleges, but may start looking for underrepresented groups there, whereas instead they should be looking out of their comfort zone, for instance seeking out colleges that are heavily weighted towards underrepresented groups. We should be going to candidates instead of just expecting them to find us, and make sure that we're actively invested in making the company diverse, focussing on inclusion (we want you here) instead of tolerance (you can come here).

Jason noted that we should be striving to make things more equitable, which will also lead to a more efficient process as a side product.

Jason described that even the job opening starts with a lot of bias, sometimes not having a clear picture of candidates, which may differ for everyone performing hiring, so you never get a right candidate that fits everyone's internal perceptions of what i.e. a "good developer looks like".

Expectations on the job spec aren't always very fair either. Jason shared this tweet, but there are dozens of cases of similar things like this that have happened before:

I saw a job post the other day. 👔

— Sebastián Ramírez (@tiangolo) July 11, 2020

It required 4+ years of experience in FastAPI. 🤦

I couldn't apply as I only have 1.5+ years of experience since I created that thing. 😅

Maybe it's time to re-evaluate that "years of experience = skill level". ♻

Additionally, folks may be interviewed for one set of tools, but then be sparingly practicing what they were actually evaluated on. Jason recommended that we should try and perform work sample tests, or use a straightforward example that indicates more how someone works with others than solving problems with skills that aren't representative of their job. I'd personally recommend listening to this episode of The Changelog with Jacob Kaplan-Moss around his writing on work sample tests for more detail.

It's important to make sure you understand the role at the start, state the actual requirements the role needs rather than a shopping list of everything you wish you had. Then, make sure you look at whether you've got any gendered language, such as "you'll be the go-to guy", "leadership material" or "assertive", for instance using Totaljobs' Gender Bias Decoder.

Once the role is out, it's important to work out how you're going to screen candidates, because you can't interview everyone, but also you shouldn't be overscreening candidates. But don't just choose the folks you like the most, or fall into pedigree bias, instead focus on the skills they have rather than just looking at the big company names or education they've received. They warned against using AI to perform any screening, because AI models are only as good as the data, and often, there's a lot of unconscious human bias that'll lead to there being algorithmic bias. They also noted that referrals don't generally lead to better employees, which I thought was interesting.

Jason talked about the fact that interviewing is a skill of its own, both on the candidate and the interviewer's side. Practice is especially a good indicator of being able to get the job - and why in the past I've recommended colleagues and friends have a "practice" interview through another company before they go to "the" job they want - and Jason mentioned that candidates that complete 3 practice interviews are 2x as likely to succeed in an interview, and 6x more likely to get the job. They shared Karat gives the opportunity to "try again" and is a huge opportunity for candidates to take an interview they felt went poorly and try it again. They noted that it doesn't even need to be taken, psychologically it just gives candidates a bit of a safety net of knowing that they can redo it. They shared that, of the 15-20% of candidates that do take the option to redo their interview, 60% of them do better in the repeat interview.

Jason also noted that it's very important to have a structured set of scoring, where you have a set of grading and specific questions around job-specific skills. This allows you to also decouple assessments from evaluation, where you can't (unconsciously) grade someone down because "they weren't clear in their answer, because they had a strong accent", because that wouldn't fit within the grading criteria.

Jason also warned against hidden assessments, for instance if you had an interview question around an implementation of Conway's Game of Life, any candidates who had already seen the game would have an advantage. Instead, focus on problems that would not need any level of domain knowledge to solve.

It's also important to note that being able to read someone's mind should not be a competency, so candidates shouldn't need to be implicitly guessing at what an interviewer is asking. Provide the space to candidates to feel like they can ask questions, if they are allowed, and make sure that you're not withholding information, because you wouldn't likely do that with a coworker, and it's especially poignant when you're holding all the power as an interviewer. There can be rubric or guides in your interviewing material for what points you need to offer assistance, and if taken, how much impact that has on scoring.

When it comes to the offer, Jason reminds us to make consistently fair offers, not trying to manage costs by seeing if you can cheekily undercut them. At this point, you should be seeing them as an employee, not a candidate, and remembering that this shows them what you're like as a company. A colleague of mine once told me that they knew that their manager had given them a worse deal than one of our other colleges because they were on a visa, which still infuriates me to this day. Jason notes that doing things like this will make the employee in question feel less included when they find out they'd been ripped off, and with recent laws and guidance around salary transparency, as well as workers being more visible about their own salaries (like my own), compensation is more open than ever, so it's only going to come back and bite you. Finally, they reminded us that we're being equitable not equal, so not everyone should be on the same compensation, unless they're at the same level and competence in the interviews.

Jason went on to mention that the hiring process doesn't finish at the offer, but once they're embedded in the organisation, so you need to make sure that you set up the new hire to succeed, with a personal onboarding plan that's targeted to the things you learned through the interview process with their strengths and development opportunities, assuming competence and giving them the resources they need to really excel.

Jason recommended that the first step is to move to structured scoring, and then the next step is whatever you can meaningfully make as your next step.

Jason finished on the note that equity is hard! It's hard to go against common practices and it'd be easier to do it with a "gut feeling" instead of a rigorous process, but everyone benefits from an organisation that's equitable.

How to effectively "Spike" a complex technical project

Aditya Bansal spoke about how there's no great "how to start a technical project" guide, and that often you have to find the known unknowns and unknown unknowns before you can get started, using a spike.

I'm a big fan of spike work to break down unknowns and help you better understand the work you're going to commit to, or just give you a safe timebox to work on a piece of work before you need to rethink your time commitment, and I was agreeing with a lot Aditya was saying.

I was especially interested in how he, in a Kotlin project, would use annotations to drive new code into three buckets:

- what's new?

- what's being modified?

- what needs further discussion?

This would then be used as part of the refinement for the real implementation. Aditya stressed that you should assume all the spike's work will be throwaway, so not to try and write production-grade code, as well as trying to not solve for every case imaginable, but instead focussing on the cases that will make the outstanding work much more manageable.

The 9.1 Magnitude Meltdown at Fukushima

Meri Williams, the conference MC, urged that everyone try not to take notes and just experience this talk. This was absolutely the right call, and Nickolas Means' talk was excellent.

Nickolas took us through the 9.1 magnitude earthquake and subsequent Tsunami that caused the nuclear meltdown at Fukushima.

Having barely surface knowledge of the disaster, this was fascinating, especially due to his incredible storytelling skills, and gave us a great insight into the way that the disaster unfolded, and how it was luckily stopped.

Throughout the talk, we could see how management styles by Prime Minister Naoto Kan and plant manager Masao Yoshida. There were so many times you could feel "this is what you shouldn't do" when managing a situation at the best of times, let alone an incredibly high pressure life-or-death situation.

One of the last quotes he shared stuck with me:

lead by being worth following

Which in this case, was super important for Masao Yoshida, who was asking his team to literally put their lives at risk, which is a pretty tall order.

Building bridges: The art of crafting seamless partnerships between engineering, product, and design

Unfortunately we arrived part way through the talk and couldn't easily get to a seat, so couldn't take notes.

Riding the rollercoaster of emotions

Gabriel Michels shared a story of a time where emotions ran high, and he worked to prevent those negative emotions lashing out.

Gab shared how he took a step back, reflected on why he was feeling what he was and reframed the negative thoughts as positive ones. He mentioned how in the cases where you feel triggered, don't react immediately and give yourself time to calm down, making sure you communicate that you need to take a step back. Make sure you focus on seeking calm resolution of conflict, as it's very difficult to end up with good outcomes when you react emotionally.

Gab also shared that he uses "if-then" thinking (for instance "if I run into a challenge, I'll ask John for support") to make these situations easier to deal with.

He mentioned that most of all, that it's OK to be emotional, it's how you handle those emotions that are important.

Platform engineering is all about product

Gal Bash explained how platform engineering requires product managers and just as much investment as product teams. As someone who is moving into a Platform engineering role soon, this was super interesting.

Gal shared a bit around the progression from Dev and Ops teams being completely separate, to having the "DevOps team" antipattern, to teams starting to be more DevOps, to having SRE teams. But in all of this, Gal noted that there's a lot of cases where this just ends up with Dev and Ops teams of the past becoming Dev and SRE teams of the now.

Gal gave an explanation of what platform engineering is to them, and how it's about providing great enablement opportunities for the rest of the organisation, often building "golden paths and paved roads" to make it easy to do the most secure/cost-effective solution with the best developer experience, while responding to feature requests.

Gal gave an example of investment in some local tooling to improve working with large AWS datasets, which went through lots of effort to get it working, but when it was released ended up unused, because it didn't actually solve a problem for folks, as they had a reasonable workaround.

Instead of building interesting tools to us as platform engineers, we should focus on a problem-first mindset, focussing on solving things that actually matter to teams. Additionally, make sure you're targeting the right level of engineer - are you building tools for power users? Occasional users? How much do you need someone to read the documentation before using the tool?

Without taking into account the problems we're trying to solve, and the users, we can end up many months down the line with nothing to show for it. Gal reminded us that we can be Agile in Platform teams, too, and should be delivering quickly, learning and iterating, and making sure we're continually building the right solutions.

Gal shared that there are a few reasons that companies underinvest in their platform teams by not giving them product leaders:

- on the assumption that "everyone will use the platform", which Gal noted is a way to rob us of a really great metric - usage of the platform - which is a really key indicator of whether we're building the right things

- believing that "Engineering Managers can do it", of which Gal thinks is unreasonable on top of the work that Engineering Managers do anyway, but also because it's under-appreciating the value that a product manager can do

- assuming that "developers know what developers want", without appreciating the depth of understanding and distilling users' feedback requests, moving to a solution that works for most users, rather than trying to please everyone, or just a vocal minority

- because it costs too much, which Gal notes is a frustrating case because it leads to engineering team(s) doing the wrong things because they can't be given a single person's extra time

I liked the takeaway that product managers are great, and having worked with some really great ones over the years, I absolutely agree, regardless of where in the organisation you are!

Cultural post mortems: an approach to learning and recovering when your people systems fail

Winna Bridgewater shared a story about the lead up to a difficult situation, and steps taken to remediate it.

Winna started off by describing complex adaptive systems and complexity science, and how a complex adaptive system can be much more resilient:

- systems - coordinated action towards some purpose

- complex - many varied relationships among parts of system

- adaptive - agents make up systems change and evolve in response to new conditions in environment

Winna took us through the build-up to the moment a team member addressed the rest of the team with "I feel really surprised by this update. Actually, I feel upset, excluded, and disappointed." and the immediate action that came from it. We could then learn how lots of small changes over time had arrived at this point, and led to this becoming a larger issue than it could've been if things were within normal functioning parameters.

Winna noted that we should try and do what we can to keep our systems on the right track, moving towards our goals together.

Strategies for succeeding as a underrepresented engineering leader

Rafia Qutab Kilian shared some strategies she's found has helped her, and that others may find useful too.

Rafia started off by discussing how leadership is a learned skillset, not something everyone can just switch on, and that it's often (consciously or subconsciously) that companies will not think of underrepresented groups as leaders.

In situations like this, underrepresented groups will need an advocate to make it more likely for them to get the opportunities to prove themselves. This can come in two forms - mentorship and sponsorship. Rafia explained that mentorship is largely guiding (technical and non-technical) work-related issues, whereas sponsorship is more than that, by supporting you and advocating for you to work on projects or be moved into prominent positions.

Rafia recommended you assess prospective companies the same way that you would assess a neighbourhood - would you feel safe? Is there a welcoming community? Do you see people like you at all levels? Making sure that you would fit in the organisation, with room to grow and be yourself.

Rafia also recommends not joining a company alone, but working to bring a few others along to support each other.

And once you have joined, you'll notice that most companies focus on the technical onboarding, not managers - as we found in another talk at LeadDev by Daniel Korn. This means more onus is on you as a manager, so you need to work to build your network, build your relationships and trust across the organisation.

Rafia chatted about how she's learned to make sure that you learn to practice boundaries. She mentioned that her "personal life is personal to friends and family" and that otherwise, discussions at work are just around work. This is especially important as a manager to make sure that you keep the boundaries between the manager and the reports.

Finally Rafia suggested that instead of being complacent, you can take a leap of faith to find more opportunities inside or outside of your organisation to improve your career chances.

Finally, she left us with this quote by Carl Sagan:

Exploration is in our nature. We began as wanderers, and we are wanderers still. We have lingered long enough on the shores of the cosmic ocean. We are ready at last to set sail for the stars.

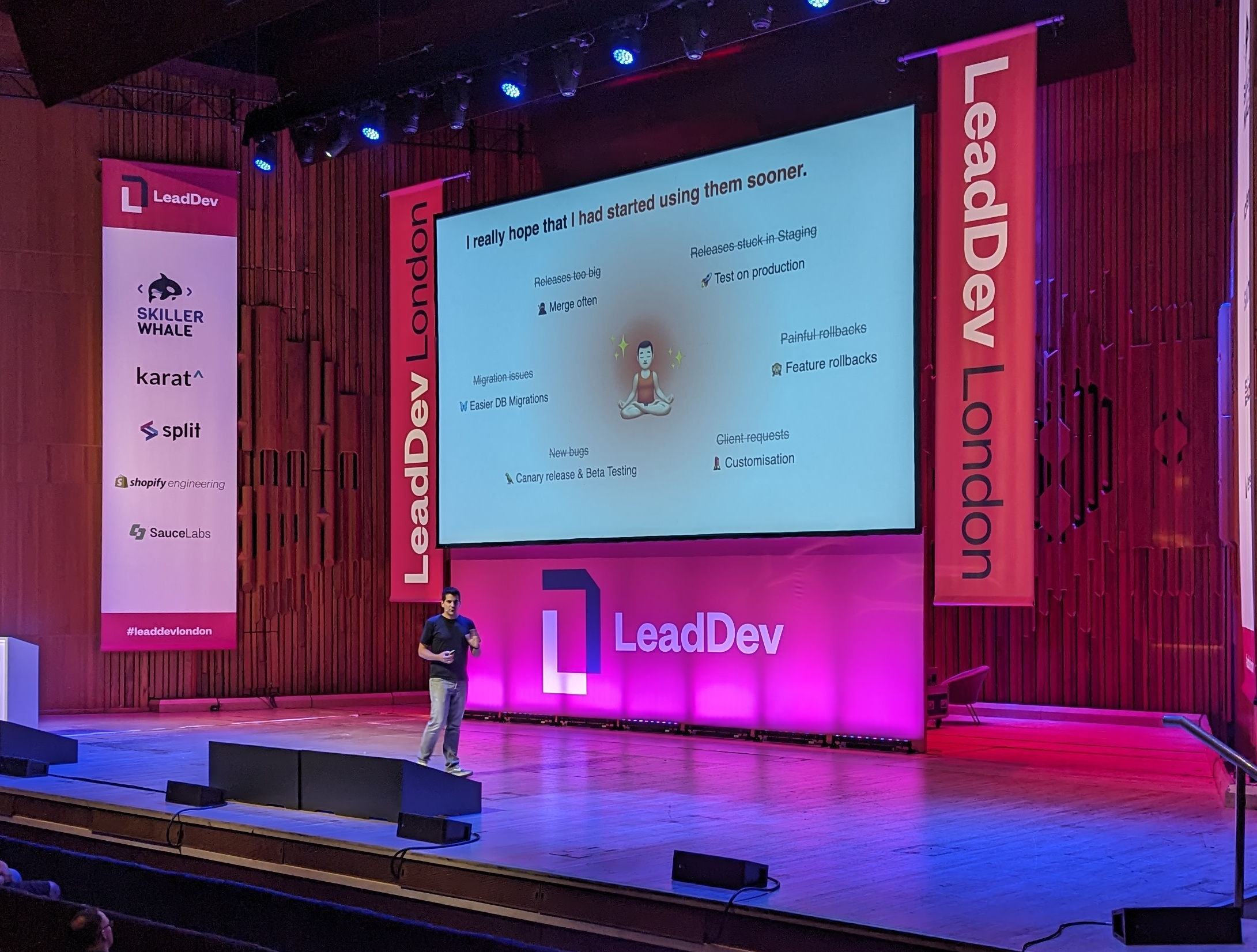

Feature flags unleashed

Roger Gros spoke about the power of feature flags and some of the pros and cons.

I've been a huge fan of feature flags and experimentation since joining Deliveroo, where it's been the first time I've done it in my career, allowing shipping features incrementally to employee-only, per-market, or on a staged rollout.

Roger mentioned that to have a reasonable feature flagging setup, the system you're using needs to:

- be fast and convenient with no boilerplate

- have built-in support for dimensions or segmentation

- have a management tool that can be used by technical and not-as-technical folks alike

Roger discussed how it can be great to have feature flags in your arsenal, because

- you are able to merge more often, with features left dormant

- you can perform more complex database migrations one client at a time, instead of all in one go

- you can perform canary or beta releases

- you can test in Production - the only production-like environment you'll ever have

- you can roll back a single feature instead of a full service

- you can perform more customisation

However, it can also be a little risky, as you may be breaking existing behaviour so measuring the impact on a rollout - and preferably automagically rolling the flag back if error rate gets too high - is key.

Longer term, the operational complexity can get quite high, especially when you have a bit of a combinatorial explosion of features across your tests, requiring you have good coverage of what happens with and without the flag. This can be simplified if your flags are short-lived, and once the experiment has finished, you go back and clean up existing feature flag code.

And finally, there's work that's required to initially invest into setting up feature flagging capabilities, so if you haven't set it up before, or aren't well versed with it, it can be a bit more of a burden.

Roger noted that despite some of the potential issues, he wish he had started them sooner, and that it's a great way to make you feel like you've got superpowers 🦸

Build a data-driven on-call workflow for your team with atomic habits

Bianca Costache took us through how her team has gone from some very difficult times of on-call, to times with dozens of pages in a given day, to a much more reasonable and chill time.

Bianca took us through the journey on one of her teams who were owning some of the digital experiences at Adobe that suddenly became more popular during the COVID19 pandemic. This required the team needed to upskill and handle a lot more load, but had a little bit of learned helplessness dealing with a lot of pages. Bianca shared that instead we should be data-driven in our approach to making on-call nicer, leaving space for learning and improvement, and give the team a set of shared accountability and empowerment to be able to enact change.

Through this process, she shared that the key questions to ask are:

- Why is on-call bad in your team?

- How can we make steps to improve?

- What were the results of these actions?

Bianca shared that we can use atomic habits, via the book Atomic Habits, to make changes to our on-call:

- make it obvious

- make it attractive - empower the team's ability to act

- make it easy

- create space for on-call reflection

- what were results of previous action items, what can we do next to improve things

- make it satisfying

- let the data reward you - it's nice to see clear and tangible results of reduced pages over time

I really liked a comment she made around how we have all these metrics like "mean time to recovery", but we don't have a "mean time to sleep", which Bianca then followed up with this tweet from Gergley:

People don’t just leave managers: they leave shitty oncall rotations as well.

— Gergely Orosz (@GergelyOrosz) February 11, 2022

She also shared this quote by John Cutler:

You can only build positive habits when your team has bandwidth. Those who make progress typically figure out how to persuade people (including their managers) to slow down to speed up

This was an interesting talk as someone who's spent most of the last 7 years on-call for services. I'm fortunate that the team I'm on right now has quiet on-call shifts. But this is largely after a period of time where there were fewer folks on-call and pages were much more frequent, as well as because in Care we're downstream services, so (usually) only get large amount of traffic or big incidents when something else has gone bust. Something I like that we've recently done is move from 1 week rotations to a 3 day rotation, which makes it much less impactful to our lives, and that we prioritise "repair items" out of incidents to make sure that we do end up fixing the problems, or adding preventative measures to reduce impact in the future.

Keeping your team health after a layoff

I'd been interested for this talk since I'd seen the agenda, and with being directly impacted by Deliveroo's layoffs, I was interested in what knowledge would be applicable to recovering from the situation. Unfortunately it was more aimed at conducting the layoff than picking up the pieces afterwards.

Leandro César Silva shared some top tips around how, as engineering leaders, to make it possible for the team to move forward in a healthy and efficient way.

When preparing the layoff, Leandro suggested that you plan what work can be dropped to allow folks to process the news. He recommended drafting communications ahead-of-time, drawing up several scenarios and expected team structures going forwards, and looking at the diversity of teams before/after. I believe this is less relevant with the UK's more stringent approach to redundancies and how the pools are approached, but it was still interesting. He also recommended to chat to direct leaders roughly a week before, so they're aware and can raise questions in time. If you're a direct leader being told about layoffs, Leandro recommended that you become aligned with the company-wide communications, take some time to accept it, and then look at how to reorganise ongoing work to give space to the team.

As the layoff is ongoing, Leandro recommended several tips for communication, starting with letting the impacted people know immediately, letting them know how the company can support them in this time. Once they're aware, it's worth telling the company why it happened, what led to these situations, and in my personal opinion, what responsibility is being taken for it. Then work to set expectations of reduced work and space given to folks affected within your teams. Finally, make sure that your 1-1s are focussed on talking about the situation, how you can better support folks, and doing what you can to help folks through this all.

Leandro shared that it's important to not sound like a robot delivering the news, and that you have a narrative that explains the why, being as honest and transparent as possible. I can see this being a huge thing, because if the reasons for a redundancy don't make sense, everyone feels a little more put out by them. In markets or situations where there are not consultation periods, give folks time to say goodbye. Leandro also mentioned that you should not immediately make other big changes, such as requiring everyone start work on a big high-priority piece of cross-organisational work.

Leandro talked about the fact that emotions will be running high, and that as leaders it's important to be there for people, as ever. For the folks who have been fortunate to stay, make sure that you focus on retention, recognising great work, reinforcing any benefits available, and even looking if you can rebalance stock options (if applicable). There may be cases that you can start projects internally to give folks a good chance for career growth or a chance to work on different things, but also make sure to give folks a chance to take time off and have some space to themselves.

Something mentioned in passing a couple of times through the conference was that "you can't do more with less" and that by trying to do so "that's against the laws of physics". It's really important for engineering leaders to remember this, remembering that folks are/have just gone through a pretty difficult time, and then trying to squeeze them for more work isn't at all a rewarding behaviour.

Something very nice about my part of the organisation's local leadership was that they were really empathetic, giving us space to work on backlog projects that would give us a chance to practice our skills in different domains or tools (for the likely job hunting during/after the process had concluded) while still be moving towards work that would benefit the org long-term. It wasn't until they could no longer shield us from a mandatory cross-org project that was pushed from on high, at which point engineering leaders and Staff+ engineers worked to shield us from as much of it as possible, so we could focus on doing what we could do, and not worrying about any of the project management or deadline side of things.

Parents who code: How to welcome your developers back after parental leave

Sinéad Cummings took us through a really great talk about setting parents up for success, instead of them coming back and leaving because of lack of support. She noted she's written about in more depth on the Opencast Software blog, which is absolutely worth a read.

This was a really great insight into what it's like to be a kick-ass engineer to going out on parental leave, and the struggles you can face coming back to work without a good night's sleep in a year, where there's often not really any real support for reintegrating again, very little fanfare (if wanted) for returning, and that would end up with parents leaving the company.

Sinéad discussed just how much can change in a year, with each tiny or larger change being done incrementally, slightly moving the needle for the team. However, as someone returning back after a year, you will have to absorb it all at once, understanding the new state of the world.

Sinéad mentioned using Keep in Touch days to their utmost, choosing a buddy in your team to be your advocate whilst you're gone. This buddy can make sure to help drip feed the changes that have been occurring in a more manageable quantity, slowly over the time they're out on leave.

Sinéad also mentioned to take notes, record big decisions, and I can imagine this being a particularly great practice generally, especially when you have folks in your team who may be off with chronic illness, as well as just generally being a good practice anyway, as well as onboarding new folks to the team.

With folks returning to work after their long period of leave, it's super important to have a plan, with meaningful and measurable goals that can be cause for success. She noted that it's also important to chat with them around whether they want to be involved in sprint work altogether, be counted in sprint velocity, dive straight into projects, spend some time catching up on the new state of the codebases, and other things that will help them better focus on their return.

Sinéad commented on the alarming increase in the cost of childcare at the moment and how it's now a big choice for parents as to whether to return to work in the end - if we're not supporting their return and setting them up for success, we're making that decision much easier for them.

And most importantly, chat to the folks who are just about to / have recently gone on parental leave to make it better.

Creating inclusive career ladders

Sally Lait took us through how we can build career ladders that work for everyone.

Sally noted that we should be building and treating levelling guidelines or career ladder documents as a compass not a map. However there are cases where these guidelines can be interpreted as more of a checklist than guide, which means you can end up getting a very specific, over-optimised view of what "good engineers" look like, enforcing biases or norms and ends up losing out on lots of other amazing strengths that are simply not rewarded.

This could be a case of rewarding firefighters rather than fire preventers, or not rewarding glue work.

Sally mentioned that it's very important to check the expectations you have for roles and determine if there are biases and whether you are building inclusively into the roles. For instance:

- "leads incident response" may not include Autistic folks or people who aren't outwardly confident

- "participates in on-call" may not work for folks who have a partner performing shift work, and a young child

- "presents in all-hands meetings" does not include folks who aren't comfortable with public speaking

- "challenges others effectively" is generally more gendered, where men are happier to challenge others

We can also replace specific actions with a more general behaviour, for instance "gives talks" can be replaced with "shares knowledge and level up others", or "shares clear opinions in team meetings" can be replaced with "helps team understand impact of other choices". This ends up still including the more neurotypical or dare I say "normal" view of things, as well as including others' behaviours, with no detriment to anyone.

Sally also shared how the way that the judgement for each capability is taken into account is important, quoting statistics about different demographics receiving significantly lower positive feedback compared to others.

Sally noted that "time is relative" and that being very prescriptive of "this capability must be done for 6 months before promotion" can harm folks who are working part time or reduced hours, are off on sick or parental leave, or may be dealing with moving goalposts in the company's priorities, constantly shifting their ability to achieve their goals. She also warned that on the flipside, we must be cautious not to promote based on "potential" alone, as that can lead to biases, and that if we focus on time-based objectives, we can use measures like "for multiple quarters".

Sally spoke about how "consistently" is hard to define when you have to take into account folks with executive function or focus issues, like with ADHD, as well as people with less visible conditions like chronic fatigue, is going through a turbulent position with their partner, and can all be making a big impact on their performance.

Sally finally described that we should be looking at outcomes achieved, instead of "has shown they can perform for a minimum 6 months", as this doesn't support folks who may have an illness or may be on reduced hours, but by and large do fit the requirements that have been required of them.

Finally, Sally recommends we question whether our frameworks are not working and for whom, scan for consequences of those gaps and ensure a diverse group works to rectify it, making sure that we get feedback and iterate over it. It's not easy, but it's the right thing to do, and can't be achieved by just copying someone else's homework.

Building for the Underserved, Solving for All

Serah Njambi Kiburu's talk was around how accessibility and internationalisation is incredibly important, and by building solutions that support a range of disabilities or diverse needs, we better serve everyone.

Something I remember from a talk I heard a few years ago was that you're not needing accessibility tools yet but being hungover, or carrying a child in your arm, or walking a slightly excitable puppy are all areas that you can be affected even if you're not physically disabled.

Accessibility isn't also just for physical needs, but includes hidden disabilities like ADHD, Autism, chronic pain, through to improving life for non-native speakers who may miss language or cultural cues.

Serah shared some great examples of how making changes to improve accessibility for some can benefit those who aren't being targeted by the changes either.

She mentioned that for those of us travelling home after the conference with suitcases, we'd be benefiting from ramps installed for folks with limited mobility. Alternatively, the closed captioning available during LeadDev was excellent for folks who were hard of hearing or deaf, as well as folks who didn't have English as a first language, or who just missed one of the four books a speaker just reeled off too quickly to write them all down.

The key takeaway is that accessibility is everyone's responsibility, and we should all be doing better, because at some point we'll be needing these accessible tools ourselves.

Driving positive change through performance improvement plans

Cristina Yenyxe González García gave an interesting talk around a difficult area in engineering leadership - dealing with times where someone may not be performing well enough. This was interesting as someone who's not an engineering manager, but can empathise with both sides of this difficult conversation.

Cristina discussed how this is never a fun conversation and can lead to a significant shift in the relationship between manager and employee, especially if not handled well and because some folks see needing to go onto a performance improvement plan (PIP) as someone almost guaranteed to lose their job.

It was nice to hear Cristina's approach to making it something that can be introduced early, informally, so it can provide meaningful impact and set the employee up for success, without it being a "last resort" or a case of coming too late into the process to be able to enact meaningful change. She mentioned that often a case of simply nudging the employee by letting them know that their performance is dipping, and regularly checking in 1-1s can be a good way to keep on top of it.

If it does end up getting to the point a PIP is needed, make sure you let the employee know it's coming, and that the objective of it is to make sure that the relationship works and that we can work together to resolve it, not that it means it's going to result in needing to leave the company. By using measurable evaluation criteria, and giving space to ask questions and seek areas for support, we can make the PIP process a successful endeavour. Again, regularly checking in and making sure that there's a positive trend upwards in performance is key, before we reach the "point of no return".

Unfortunately it doesn't always work out as successful, so in this case it's worth getting a clear understanding of the process in this case, working with HR to organise who is telling the employee and any next steps needed.

But if it has gone well - and we hope it will - we shouldn't forget this, and take care to make sure that the employee doesn't start a downward trend again.

Exit plans and how to talk about them

David Kiger's talk was a really interesting concept, especially as someone who is just leaving their job, around the fact that people are going to leave, and pretending that they're not is silly. With the average tenure being less than 3 years in the Tech Industry, as well as it being incredibly infrequent that employees join a company with the intention of retiring there 40 years later, it's an important fact to realise. Instead, as engineering leaders as well as well as individual contributors, we should be a bit more honest about that fact, and cultivate a culture around being able to discuss this.

As someone who thrives in a culture where I can be a bit more honest and open - as seen with my salary page, as well as posts about my job hunt or my career progression - this greatly spoke to me.

David's talk was a well crafted story going through the process of building this culture inside Yelp through his direct team, and then across the whole org, making it a topic that can provide a huge amount of value into understanding your team's motivations, and being able to more applicably action situations for their team.

David talked about how an engineering leader hearing that a technology choice is not the right fit and may lead to a team member leaving can give them a lever to be able to find other opportunities internally. Knowing that one of your team may quit due to frustration in a spectacular state of burnout will allow you to work to manage their stress levels better. If someone would be looking at leaving for career progression, there could be opportunities internally they can be given. And finally, if it's purely a case of money, well, there's only so much the company can/is willing to do.

This was especially interesting to me as I'd kinda already had these conversations with my manager recently, albeit more pitched at moving to a different team, instead of leaving the organisation (albeit I did end up leaving the organisation) - and I'm fortunate to have a strong foundation of trust with my manager, and being able to discuss this honestly.

David also mentioned that managers are likely to see many more folks leaving the company than people will be quitting, so you can always ask your/a manager to help you navigate the process, including setting you up with practice interviews or support to get the right job for you next. It may not always be possible to be super above board with leaving - especially if it may lead to you missing out on a bonus, or may risk your visa status - but it's definitely something that can make it a better process.

David noted that whenever he's shared this with his teams, he's come with three goals for discussing this:

- reassuring his team that they still have options here, if they let their manager know

- reassuring his team that they will not be penalised for discussing or thinking about leaving

- selfishly not wanting to be surprised when a resignation letter arrives

David discussed the current macroeconomic climate, where a lot of folks may be staying in roles they are currently in, waiting for things to settle down and then may look at leaving. This was similar to during the height of the COVID19 pandemic, where there was virtually no attrition in roles, but as soon as things started getting a bit safer, The Great Resignation happened. For companies without the culture around discussing exit plans, being shocked by dozens of folks handing in their notice can be rather off-putting.

A huge takeaway from David's talk is that it's really down to trust, and if there's no trust between employee and company, let alone employee and manager, then this can't work. It's easier for folks like me or David to be able to talk about this, as we're significantly more privileged than others, but the whole point is getting your teams and organisation to the point that no matter the status of your job, you should be able to be honest and work on it with your manager.

I'd also recommend a read of a post he's previously written about this that digs into the topic in a bit more depth.

I'll definitely be taking this onboard for future roles, at least thinking about it inwardly, but also hoping to share with my managers to better manage expectations and also see if there are things we can do to address any causes of me looking elsewhere.

Orchestrating thousands of bots from the cloud

(I unfortunately wasn't around for the talk)

The awful agony of the app store: When software delivery goes wrong

Clare Sudbery took us through a great funny, but frustrating, journey of trying to build a fun game on the Apple App Store, approaching it with a lot of great engineering practices like Continuous Delivery or building out a Minimum Viable Product, but being thwarted by the processes enforced by Apple.

In conclusion

If you've made if this far - whether you skipped to the end, or you've read this all - thanks for reading!